1

/

of

4

cacheantiquessydney

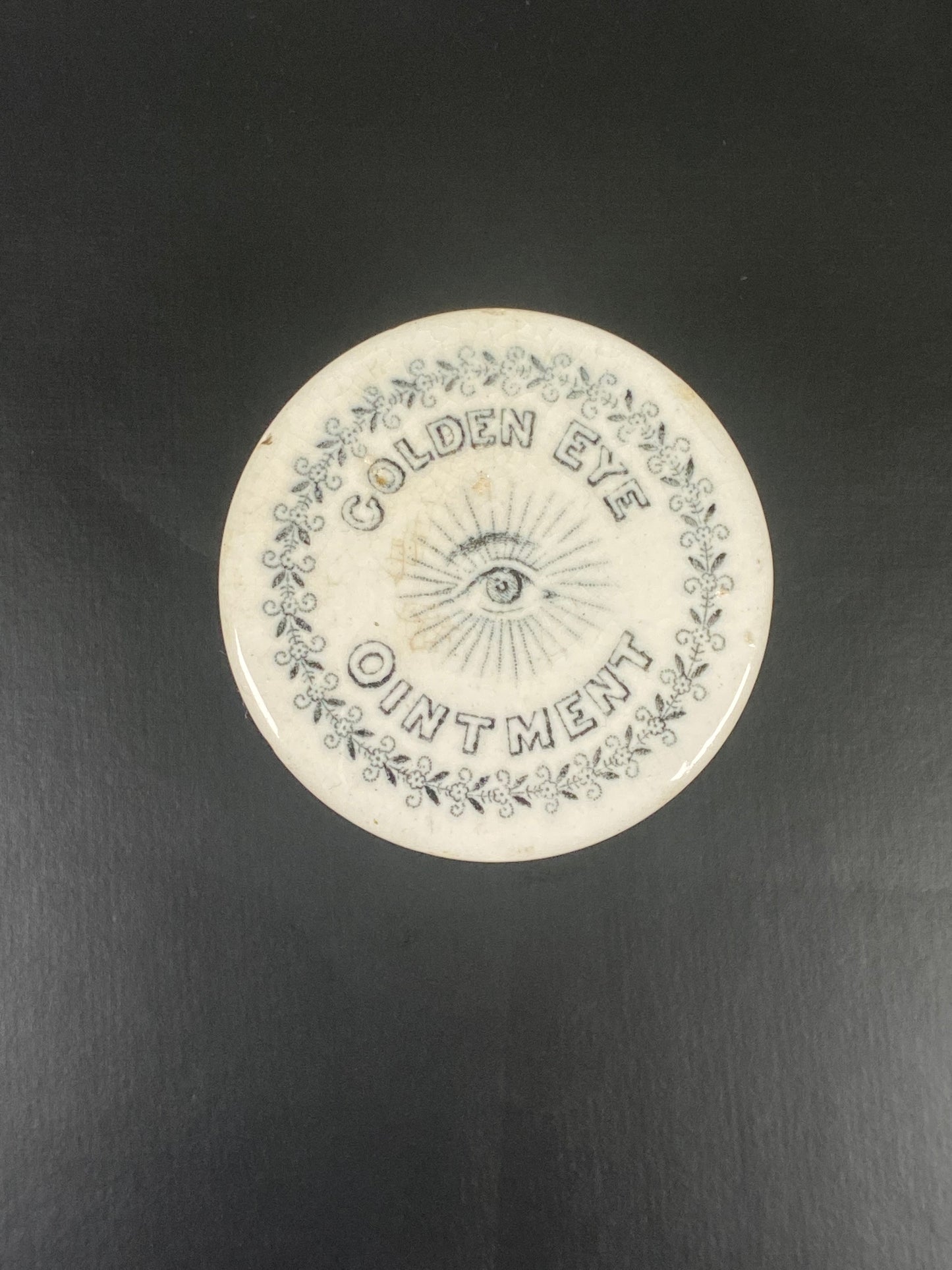

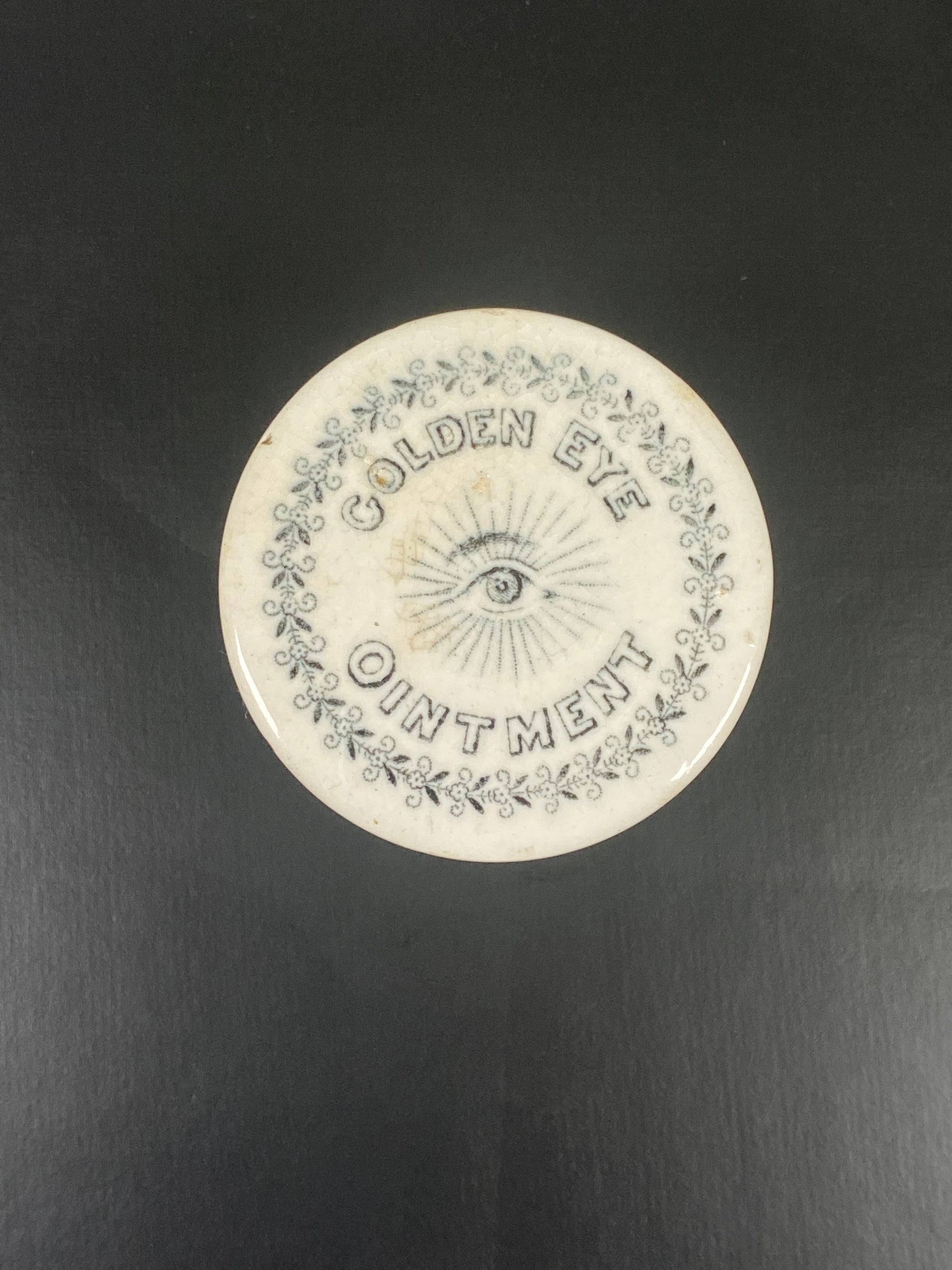

19th Century Victorian Apothecary Transferware Lidded Pot, Golden Eye Ointment

19th Century Victorian Apothecary Transferware Lidded Pot, Golden Eye Ointment

Regular price

$380.00 AUD

Regular price

Sale price

$380.00 AUD

Unit price

/

per

Shipping calculated at checkout.

Couldn't load pickup availability

This small late 19th century transferware pot of Golden Eye Ointment contains a tale with military exploits, family heirlooms and a dash of medical quackery to boot.

First formulated by a Dr Johnson in 1596, it rapidly became known (and was touted) as a cure all for eye disorders. Upon his death the recipe was passed to the Hind family. In 1794 William Hind gave his daughter Selina the treasured recipe as a wedding present when she married Thomas Singleton.

This would have been a footnote in history- then in 1798 the British army sallied against Napoleon Bonaporte in Egypt. Soldiers who had hitherto fought in Europe were woefully unprepared for the desert climate, resulting in temporary blindness due to sun glare and the hot sand. The British army found itself in dire need of eye curatives, and Singleton’s ointment rose to the occasion. In 1799 Thomas passed, leaving the recipe to his oldest son William, who would receive a testimonial from the War Office signed by His Royal Highness the Duke of York, on behalf of the many British soldiers who were “perfectly cured” by its use.

The ointment’s popularity proved timeless, and the eye pedestals the ointment previously came in were replaced by small lidded pots in the 1860s-70s. These porcelain pots were manufactured by Mid-Lothian Pottery Co., Portobello, Edinburgh until Golden Eye ointment was discontinued sometime in the early 1920s, when concerns began to arise over its use of mercury. That’s right- the miraculous ointment was quicksilver, which was produced by heating it with nitric acid. The resulting salt was mixed with clarified butter to make the ointment, to be rubbed on the eyelids at night.

A small but remarkable piece, and a similarly remarkable bit of history to boot. The eye motif version of these pots is particularly rare and desirable among collectors.

Price marked at AUD$380

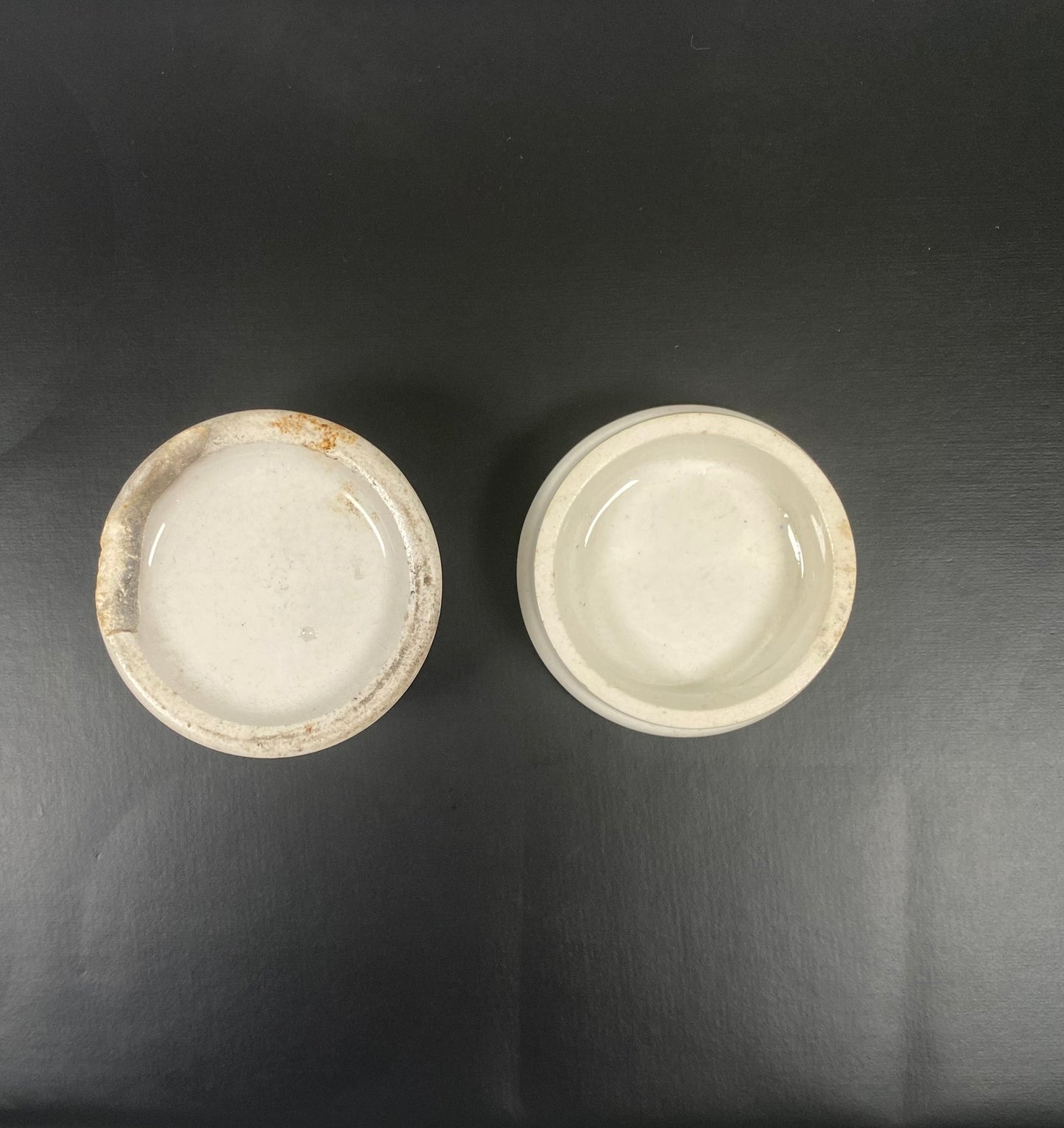

Measurements: 5cm dia., 3.2 cm high

Good antique condition. These pots are often chipped from use and/or found buried in mud. This is one of the better examples we have found, with wear as pictured.

First formulated by a Dr Johnson in 1596, it rapidly became known (and was touted) as a cure all for eye disorders. Upon his death the recipe was passed to the Hind family. In 1794 William Hind gave his daughter Selina the treasured recipe as a wedding present when she married Thomas Singleton.

This would have been a footnote in history- then in 1798 the British army sallied against Napoleon Bonaporte in Egypt. Soldiers who had hitherto fought in Europe were woefully unprepared for the desert climate, resulting in temporary blindness due to sun glare and the hot sand. The British army found itself in dire need of eye curatives, and Singleton’s ointment rose to the occasion. In 1799 Thomas passed, leaving the recipe to his oldest son William, who would receive a testimonial from the War Office signed by His Royal Highness the Duke of York, on behalf of the many British soldiers who were “perfectly cured” by its use.

The ointment’s popularity proved timeless, and the eye pedestals the ointment previously came in were replaced by small lidded pots in the 1860s-70s. These porcelain pots were manufactured by Mid-Lothian Pottery Co., Portobello, Edinburgh until Golden Eye ointment was discontinued sometime in the early 1920s, when concerns began to arise over its use of mercury. That’s right- the miraculous ointment was quicksilver, which was produced by heating it with nitric acid. The resulting salt was mixed with clarified butter to make the ointment, to be rubbed on the eyelids at night.

A small but remarkable piece, and a similarly remarkable bit of history to boot. The eye motif version of these pots is particularly rare and desirable among collectors.

Price marked at AUD$380

Measurements: 5cm dia., 3.2 cm high

Good antique condition. These pots are often chipped from use and/or found buried in mud. This is one of the better examples we have found, with wear as pictured.

Shipping & Returns

Shipping & Returns

Share